Syncope is a relatively common condition in children and adolescents. Most children with syncope do not have serious diseases and their prognosis is generally benign. However, in certain patients, syncope may be the first presentation of a serious cardiac pathology. Therefore, the understanding of its pathophysiology, causes and investigative work ups are important for general pediatricians dealing with this entity.

Syncope is a transient loss of cerebral function due to lack of energy substrate (low blood pressure, decreased oxygen tension or low blood glucose). The results are loss of consciousness and postural tone.

Normal brain function requires adequate blood pressure, oxygen supply and energy substrate (glucose). Inadequacy of any one of these factors (due to, for example, hypotension, hypoxia or hypoglycemia) can lead to syncope. Other conditions that mimic syncope include abnormal brain discharge (seizure), vestibulocerebellar migraine, hyperventilation syndrome and pseudo-syncope (psychogenic syncope).

Syncope in children most commonly occurs from a reflex transmitted via the autonomic nervous system (Bezold-Jarisch reflex) that causes peripheral vasodilation or bradycardia, or both (the so called “vasovagal” or “neurocardiogenic” syncope). In a small number of patients, hypotension and syncope may result from cardiac pathology (cardiac syncope). The distinction between these 2 etiologies is important and is the main subject discussed in this article.

It is uncertain how frequently children have syncope, partly because most children with a single episode of syncope do not come to medical attention. One study showed the incidence of children and adolescents with syncope that came to medical attention to be 126/100,000.1 It was estimated that up to 15% of normal children would experience at least one syncope before the age of 18.1 Most of these children had neurocardiogenic (vasovagal) syncope and were otherwise healthy. The peak incidence of syncope in children occurs at around the age of 15-19 years with a higher prevalence in females.2

The usual form of neurocardiogenic syncope is caused by stimulation of the intramyocardial mechanoreceptor (stretch receptor or C fiber) as a result of forceful myocardial contraction from various etiologies such as decreased cardiac preload from prolonged standing. A neural impulse from the myocardium is sent to the brainstem, causing a reflex that leads to a withdrawal of sympathetic stimulation and/or an increase in vagal tone, resulting in paradoxical bradycardia and/or vasodilation. This is called “Bezold-Jarisch reflex”. This mechanism explains syncope occurring in children while standing in line at school in hot weather or while standing in a church. It also serves as the basis for treatment of neurocardiogenic syncope with medications that decrease cardiac contraction such as beta adrenergic blockers or medications with vagolytic property such as disopyramide.

Apart from prolonged standing (especially in hot or crowded places), there are also other afferent pathways that may trigger neurocardiogenic syncope. For example:

Because neurocardiogenic syncope is common in children and adolescents, most often the diagnosis is made from a clinical ground. The usual descriptions of children who experience neurocardiogenic syncope are as follows:

Heart diseases that cause syncope in children are generally severe structural defects, coronary anomaly or aneurysm, or are arrhythmia syndromes that cause ventricular tachyarrhythmia. All of these etiologies can lead to sudden cardiac death. Examples of these conditions are left or right-sided heart outflow obstruction, severe pulmonary hypertension, coronary obstruction causing myocardial ischemia, cyanotic spell, sick sinus syndrome, heart block, long QT syndrome, catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome and Brugada syndrome.

b. Heart block. Presence of syncope with complete heart block is ominous. Patients with heart block can have syncope from prolonged asystole or bradycardia-induced VT. c. Sick sinus syndrome

6. Other rare causes of cardiac syncope include mitral valve prolapse, left or right heart inflow obstruction

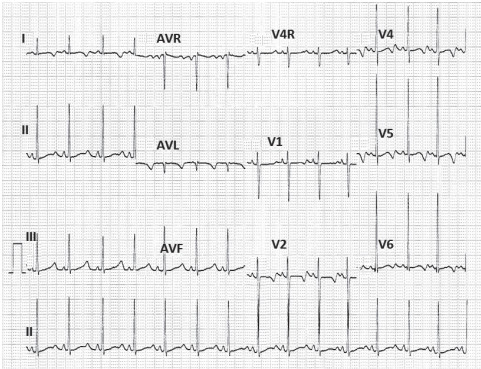

Figure 1: Long QT syndrome. This child has a family history of long QT syndrome and neurosensory deafness.

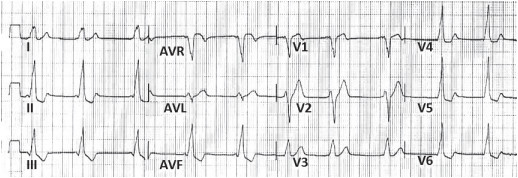

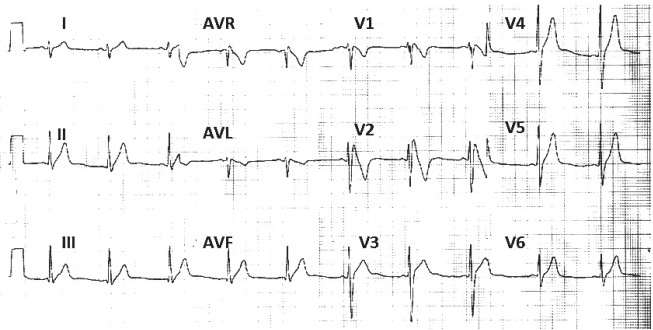

Figure 2: Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. There are delta waves (slurring of R wave) and short PR interval.

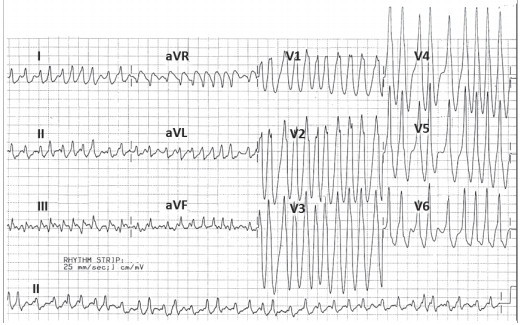

Figure 3: Atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular conduction via the Kent’s pathway which makes the 12-lead EKG look like ventricular tachycardia. Rapid ventricular conduction and fast ventricular rate may lead to ventricular fibrillation, syncope or sudden death. (Courtesy of Dr. Somchai Prichawat, MD)

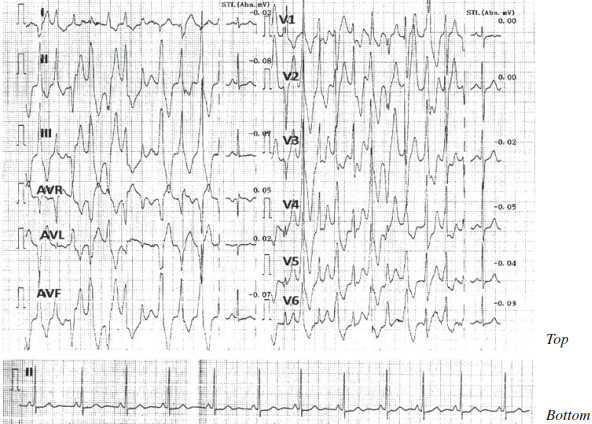

Figure 4: Catecholaminergic polymorphic VT during exercise in a child who presented with recurrent exertional syncope (Top). The resting EKG was normal (Bottom). Physical examination was normal.

Figure 5: Presence of right bundle branch block pattern with ST elevation in right chest leads (V1 and V2), suggestive of Brugada syndrome.

Most previously healthy children with a typical history of neurocardiogenic or vasovagal syncope can be diagnosed by careful history and physical examination. Twelve-lead EKG is recommended by many experts as a routine investigation in children and adolescents who present with syncope to rule out the possibility of heart disease.1,2,6 Apart from EKG, other investigative work ups such as EEG, Holter monitoring, echocardiogram, exercise stress testing or other specialized testings are done selectively, as dictated by the clinical setting of the patient. In general, investigative work up for syncope is indicated in children with syncope and one or more of the following features.1,2,5

The choice of further investigation(s) depends on the differential diagnosis. EEG and neurologic referral is indicated in a patient who is suspected to have seizure. The initial evaluation in children suspected to have cardiac syncope with normal physical examination begins with 12-lead EKG to look for evidence of ventricular hypertrophy/dilation, ST-T abnormality suggestive of myocardial ischemia, cardiac conduction defects or presence of arrhythmia syndrome such as long QT, WPW and Brugada syndrome. The diagnosis of coronary ischemia usually requires further investigation such as exercise stress test, echocardiogram or coronary angiogram. Resting 12-lead EKG is usually normal or shows only minor abnormality in patients with polymorphic catecholaminergic VT but the diagnosis can be made on exercise stress testing (exercise testing in patients with exercise-induced syncope can be dangerous so it should be done by an expert). Holter monitoring and event recorder (loop recorder) is useful if cardiac arrhythmia is suspected. Cardiac MRI is useful to diagnose arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia or other types of silent cardiomyopathy. Finally, an invasive cardiac catheterization, angiography and electrophysiologic study may be needed in the rare cases whereby other non-invasive testing is not diagnostic.

Tilt table testing is a provocative test for neurocardiogenic or vasovagal syncope. The test is done by tilting the patient upright for prolonged period of time, with or without administration of a medication that increases cardiac contraction (to stimulate myocardial mechanoreceptor) such as isoproterenol infusion or a medication that decreases cardiac preload, such as sublingual nitroglycerine. Because the specificity and sensitivity of tilt table testing for the diagnosis of neurocardiogenic syncope are not very high6,7, the test is usually done when the diagnosis of neurocardiogenic syncope is questionable, such as in patients with unusual symptoms or unusual triggering events, or in patients with recurrent syncope of unclear etiology. It must be kept in mind that tilt table testing can be positive in patients with other etiologies of syncope as well, hence the interpretation of the test must be made in light of the pretest probability (i.e. the patient’s history, physical examination and the results of other investigations). Infusion of isoproterenol or sublingual administration of nitroglycerine usually increases the sensitivity but may decrease the specificity of tilt table testing.8,9

Treatments of syncope in children largely depend on the etiology. Children with (or suspected to have) cardiac syncope need to be seen and treated by a pediatric cardiologist. Neurologic or psychiatric referrals are recommended for children suspected to have seizure or neuro-psychiatric disorders such as hyperventilation syndrome or pseudoseizure. Children with the diagnosis of neurocardiogenic or vasovagal syncope can be treated and followed by a pediatrician, unless there is uncertainty about the diagnosis or if there is frequent recurrence of the symptom.

There is no single treatment that is most effective for children with neurocardiogenic syncope. It should be explained to the parents and patient that the disease is not life-threatening although it may recur in the future and may cause injury from falling. The child should be taught to avoid the conditions that may precipitate syncope, such as prolonged standing in a crowded or hot environment, dehydration, missing a meal or lack of sleep. Drinking more water or consuming more sodium (eating salty food) may help to prevent syncope occurrence. If the child experiences a prodromal symptom, such as lightheadedness, nausea or vomiting, he/she should sit or lie down immediately (with or without the feet raised above the chest) to avoid the total loss of conscious which may cause a fall or bodily injury.There are additional maneuvers that the patient can do to abort the syncope, such as crossing and squeezing the arms and legs or squatting down to increase systemic blood pressure.1

Medication is usually reserved for children with neurocardiogenic syncope who experience frequent recurrence or those who have severe symptoms. There is no medication that has been shown to be most effective in this disease. Many drugs have been used with variable success or in some studies, even showed no benefit.10,11 These medications include beta adrenergic blockers (to decrease cardiac contraction and stimulation of myocardial stretch receptors), disopyramide (used for its negative inotropic and anticholinergic properties), fludrocortisones (to make the kidney retain salt and water), midodrine (to increase venous return by stimulating adrenergic α-receptor) and pseudoephedrine (for vasoconstrictive effect). Physicians must help patients and their parents to understand that no medication is universally effective and despite taking medication, the child is still at risk for recurrent syncope and all other measures described in the previous paragraph should still be adhered to.

Children with neurocardiogenic syncope generally have excellent prognosis. Spontaneous remission as the child gets older is common.7 The most important thing when evaluating children suspected to have neurocardiogenic syncope is to rule out other etiologies of syncope and to advise the patients and their parents on how to live with this usually benign condition.

Q1. Investigative work-up (other than history taking and physical examination) is most indicated for which of the following patients who present with syncope?

a. A 7-year old girl developed syncope while standing in line at school

b. A 10-year old girl developed syncope during venipuncture procedure

c. A 13-year old boy had syncope while standing after urination

d. A 15-year old boy had syncope while playing basketball e. Investigative work up is not indicated in any of the above patients

Q2. Which is the following is LEAST frequently seen in a child with neurocardiogenic (vasovagal) syncope?

a. Pallor

b. Cyanosis

c. Nausea, vomiting

d. Blurring of vision

e. Feeling hot and sweaty

Q3. Syncope is one of the typical presentations in which of the following heart diseases?

a. Atrial septal defect

b. Ventricular septal defect

c. Aortic valve stenosis

d. Patent ductus arteriosus

e. All of the above

Q4. A 3 year-old boy has a history of recurrent syncope (4-5 times in the past year) while feeling frightened or hearing loud noises. The last episode occurred yesterday after swimming, with the patient having tonic posturing of the extremities before gaining consciousness. Physical examination revealed no abnormality. There is a family history of unexplained death in a young cousin of the boy’s father. Which of the following investigation is most likely to yield the diagnosis?

a. 12-lead EKG

b. Electroencephalogram (EEG)

c. Echocardiography

d. Coronary CT scan

e. Intracardiac electrophysiologic study

Q5. Which of the following is LEAST likely to be effective in preventing neurocardiogenic syncope?

a. Avoid standing for a long time

b. Consuming more salty food

c. Taking more water before school

d. Taking medication with beta blockade property

e. Taking medication with vasodilatory property

Answer 1: e. Most children with syncope have the diagnosis of vasovagal or neurocardiogenic syncope with good prognosis. However, there are certain children with significant heart diseases that cause syncope. Physical examination in these children may be abnormal in cases of right or left heart outflow obstruction but could also be normal in patients with cardiac arrhythmia or coronary anomaly or obstruction. Thus, careful history taking is important for evaluation of a child presenting with syncope. The history in items A to C could be consistent with vasovagal syncope. On the other hand, a history of syncope during exertion is more consistent with cardiac syncope and requires further investigation.

Answer 2: b. Children with vasovagal syncope may have prodromal symptoms and/or signs of low blood pressure such as feeling dizzy, having blurring of vision or looking pale prior to fainting. Additionally, he/she may feel hot and sweaty, report excessive yawning nausea or hyperventilation prior to syncope. History of cyanosis is rare.

Answer 3: c. Severe left or right heart outflow obstruction can cause syncope, especially during exertion due to inability to further increase cardiac output or because of ischemia and/or cardiac arrhythmia. Left-toright shunt such as an ASD, VSD or PDA, however, rarely causes syncope.

Answer 4: a. One of the most common causes of cardiac syncope for children with no past history of heart disease and who have normal physical examination is cardiac arrhythmia, especially ventricular arrhythmia (ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation). Many of these children have inherited diseases, causing abnormal function of ion transport across the cardiac cells or within the cells. The description of this patient is typical for a long QT syndrome, which usually causes syncope during exertion or during an emotional event such as being frightened or hearing a loud noise. During an episode of ventricular arrhythmia and cerebral ischemia, tonic posturing of the whole body may be seen which could be mistaken for seizure disorder. Twelve-lead EKG usually confirms the diagnosis, however, the fact that QT interval is normal neither excludes long QT syndrome nor other arrhythmic syndromes such as catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia.

Answer 5: e. Patients with vasovagal syncope should avoid any situation that may cause syncope such as prolonged standing, especially in a hot or crowded place. He/she should avoid being dehydrated and taking more water and salty food may help preventing syncope. Most patients with vasovagal syncope do not need pharmacologic intervention but if required, medications with beta blockade or vasoconstrictive effects have been used with variable success. Other medications that had been used are fludrocortisone (to cause sodium and fluid retention) and medications with vagolytic effect.