Successful HIV/AIDS prevention and control causes a decline in the incidence of newly acquired HIV/AIDS patients. The annual mortality rate from 2000 to 2018 has decreased by 37% and 45% respectively.1 However, according to global figures the number of PLWHA remains high approximately 37.90 million, with 1.7 million new cases of HIV recorded in 2018. In Thailand, there are 480,000 cases of HIV/AIDS with 6,400 new cases of HIV recorded in 2018.2

HIV/AIDS has a significant impact on the complexity of physical, psychosocial, and spiritual dimensions. The influences on the physical result from a decline of the immunological system. Therefore, PLWHA are at risk of opportunity infections (OIs), the main cause of mortality.3,4 Psychological problems include anxiety, depression and suicidal behaviors.4-6 The social impacts are stigmatization, orphaned children, problems and financial troubles. In response, the government has invested more money in research and health care services for PLWHA.4,5 The spiritual impact arises from suffering from diseases, stigmatization, guilt, fear of death and spiritual distress.7

Spirituality has played an important role among PLWHA because it can promote peace and happiness, inner strength, understanding of the illness and self-acceptance, self-health care, a sense of compassion, purpose in life, hope, relationships and connection with a higher power, divine or God.8 Thus, spiritual well-being can assist PLWHA to confront their disease and stressful life events.8 According to the studies of Dalmida et al,9 spiritual well-being was positively correlated on CD4 cell count. Ironson et al.,10 found that spiritual well-being correlated better on the control of viral load, and slow disease progression. Besides, some research studies revealed that spiritual well-being was related to psychological adaptation, life-satisfaction, quality of life and well-being.11-14 Moreover, Ironson et al.,15 found that spiritual well-being helped patients significantly to cope, andpredicted greater survival in HIV patients.

According to literature reviews, spiritual well-being depends on a number of factors. For example, a study of Praiwan17 religious practice was correlated to spiritual well-being in PLWHA (r = 0.82, p = 0.05). Netimetee18 found that hope and social support was associated with spiritual well-being in PLWHA (r = 0.61, p = 0.000 and r = 0.44, p = 0.000 respectively). Similarly, the study of Yaghoobzadeh et al.,19 showed that hope related to spiritual well-being in patients with cardiovascular disease (p < 0.001). Moreover, Yi et al.,20 and Dalmida et al.,21 found that depression negatively impacted spiritual well-being in PLWHA. Furthermore, Dalmida et al.,9 found that CD4 cell count was positively correlated to spiritual well-being (r = 0.24, p < 0.05).

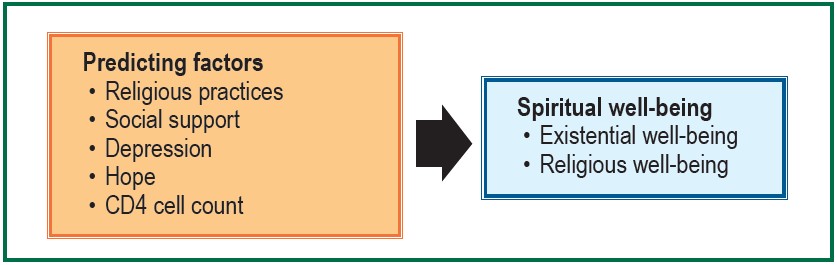

Therefore, these factors should be studied to explore their correlation and predictive power on spiritual well-being among PLWHA. The concept of spiritual well-being, developed by Paloutzian& Ellison24 was applied to the study. There are two dimensions of spiritual well-being, consisting of existential well-being (EWB) and religious well-being (RWB) (Figure 1). The findings of the study could be applied to developing a spiritual care program to promote spiritual well-being among PLWHA.

Participants were PLWHA who followed up at a tertiary hospital in the northeast region of Thailand from 1 July 2019 to 30 September 2019. Inclusion criteria:

The sample size was calculated by using G*power. There were five factors consisting of religious practices, social support, depression, hope and CD4 cell count. The effect size was 0.15, α = 0.05 and 1 – β = 95%. Therefore, the sample size was 138 cases. The samples were selected by simple random sampling technique.

Ethical considerations

This research was a descriptive predictive study and approved by the Ethics Committee, EC number 035/2562. Participants obtained information about the study objectives and processes, the advantages and risks of the study. They could withdraw from the study at any time and they enrolled in the study after having completing an oral consent form.

Instruments

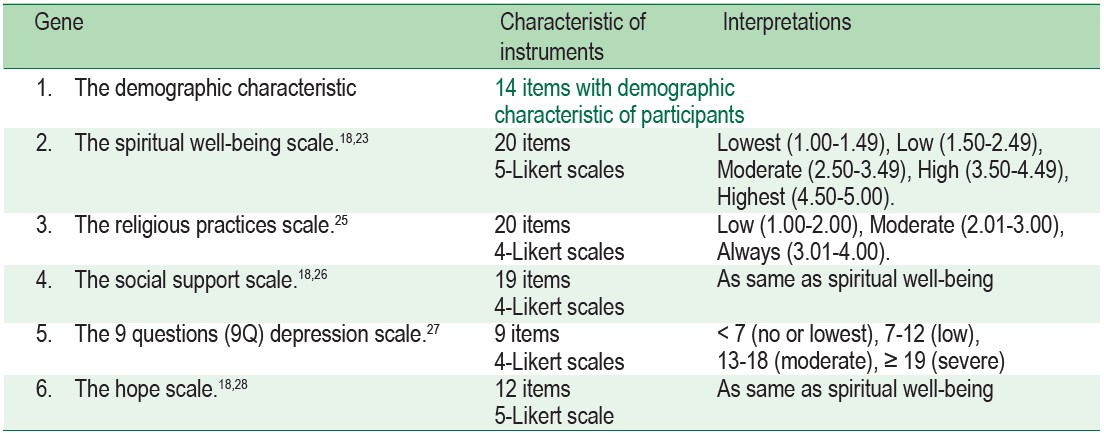

The questionnaires were divided into 6 parts. Parts 2-6 were tested for reliability by applying Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The reliabilities of the second to the sixth parts were 0.87, 0.90, 0.89, 0.89 and 0.87 respectively (see Table 1).

Figure 1: The conceptual framework for the study

Table 1: The instruments in this study, characteristic of instruments and interpretations.

Data collection

Participants were invited by registered nurses based on the inclusion criteria. Then the researcher contacted each participant privately to explain the research aims and enrolled interested participants in the study after having received an oral consent form. After this, participants answered the questions by themselves spending around 15-30 minutes. If they had any problems or could not understand any questions, the researcher was available to explain further as needed.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed by using frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation, Pearson product-moment correlation, and stepwise multiple regression.

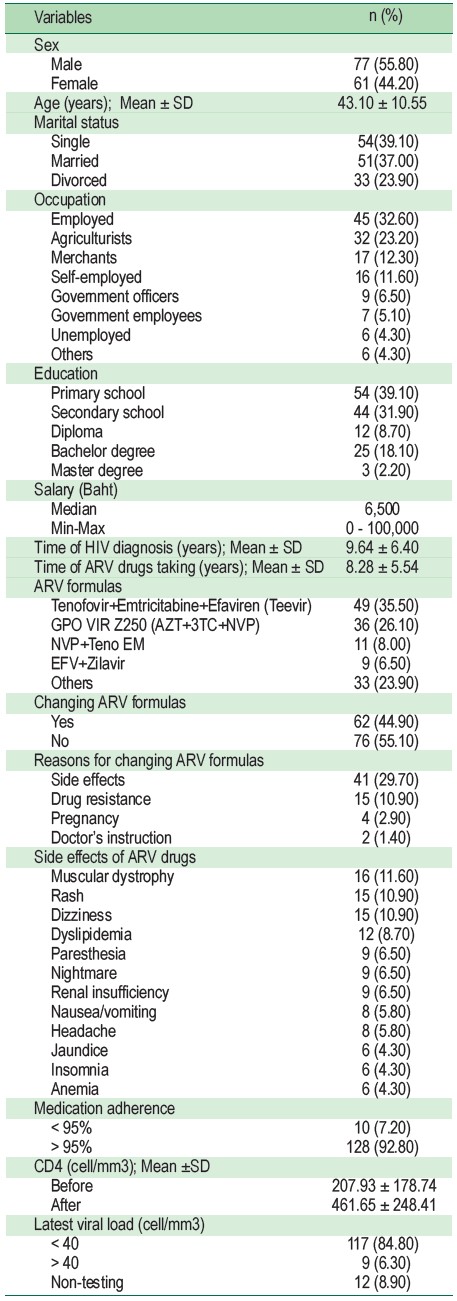

The total of participants in the study was 138 cases. Most of the group participants were male (55.80%), mean age 43.1 years old, married (39.1%), employed (32.6%), and primary education level (39.10%). The median monthly salary was 6,500 baht. The mean time since HIV diagnosis was 9.64 years and the mean time taking antiretroviral (ARV) drugs was 8.28 years. Most ARV formulas were Tenofovir+ Emtricitabine + Efaviren (Teevir), 35.50%. Some participants had changed the ARV formula, 44.90%. The main reason for changes in the ARV formula was the side effects of medication, 29.70%. The main side effect of the medication was muscular dystrophy, 11.60%. The medication adherence above 95% was 92.80%. CD4 level increased from 207.93 cell/mm3 to 461.65 cell/mm3. The latest viral load below 40 cell/mm3 was 84.80% (see Table 2).

Spiritual well-being among PLWHA

The overall spiritual well-being of PLWHA was at a high level (4.03 ± 0.55). Existential well-being (EWB) and religious well-being (RWB) were at a high level (4.03 ± 0.64 and 4.02 ± 0.57 respectively). The highest score was that religion could assist well being (4.28 ± 0.80), religious practices could assist people to find a peaceful life (4.25 ± 0.84), and a joyful life (4.25 ± 1.07) respectively. On the other hand, the lowest score was that religious belief could assist inner strength. (3.64 ± 1.33)

Predicting factors among PLWHA

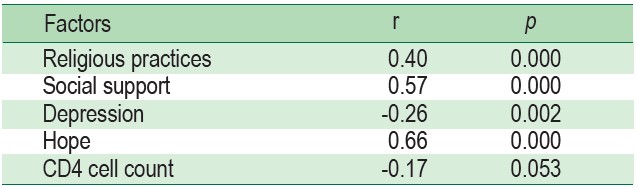

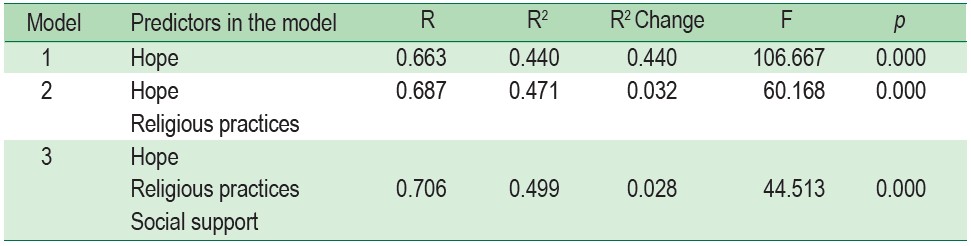

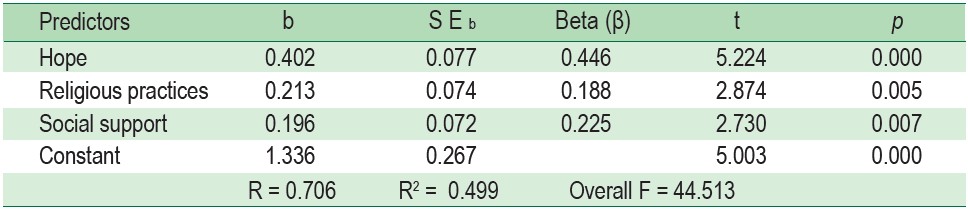

Factors related to spiritual well-being among PLWHA at the level .05 were religious practice (r = 0.40, p = 0.000), social support (r = 0.57, p = 0.000), depression (r = -0.26, p = 0.002), and hope (r = 0.66, p = 0.000). While there was no correlation between CD4 level and spiritual well-being among PLWHA (r = -0.17, p = 0.053) (see Table 3), predicting factors of spiritual well-being among PLWHA were hope (β = 0.446, p = 0.000), religious practice (β = 0.188, p = 0.005), and social support (β = 0.225, p = 0.007) (see Table 4). These predictors accounted for 49.90% (R2 = 0.499; p < 0.05) (see Table 5). The predictive equation was constructed as below.

ẐSpiritual well-being = 0.446 Hope + 0.188 Religious practice + 0.225 Social support

Table 2 : Demographic data of subjects. (n = 130)

Table 3 : Factors related to spiritual well-being among PLWHA (n = 138)

Table 4 : The stepwise multiple regression analysis of predicting factors for spiritual well-being among PLWHA (n = 138)

Table 5 : The summary of stepwise multiple regression analysis of predicting factors for spiritual well-being among PLWHA (n = 138)

Spiritual well-being among PLWHA

The overall spiritual well-being among PLWHA was at a high level (4.03 ± 0.55) both EWB and RWB were at a high level (4.03 ± 0.64 and 4.02 ± 0.57 respectively). It can be explained that most of PLWHA were middle aged (43.1 years old). Fowler29 indicated that this age is at stage five ofconjunctive faith. People will accept paradoxes and transcendence correlating reality behind the symbols of inherited systems. This is important for promoting spiritual well-being.30-31 The mean time of HIV diagnosis was 9.64 ± 6.40 years. This is long enough to promote spiritual adaptation among PLWHA. According to the study of Balthip et al.,32 which studied the process of achieving peace and harmony in life among Thai Buddhists living with HIV/AIDS for 5 years or more, achieving a level of understanding, accepting that nothing is permanent and living with contentment assisted PLWHA to achieve inner peace and harmony.32 Furthermore, the study of Saeloo39 found that there were four stages of health perception and self-care in HIV/AIDS patients with over seven years survival including:

Stage 1: Inability to adjust, having only thoughts of fear.

Stage 2: Ability to adjust and seeking for survival

Stage 3: Self-care as a means of survival.

Stage 4: Harmonious life (acceptance of HIV and death).

Most of the participants in our study did not change the ARV formula. There were no side effects from medication, and medication adherence was higher than 95% with 92.80%. These positively affected an increase in CD4 cell count and decrease in the viral load in plasma. As a result, they were healthy, improving self-care and working well. O’Brien31 indicated that the severity of illness or degree of functional impairment influenced the finding of spiritual meaning in the experience of illness. This is crucial for nurturing spiritual well-being. Three of the highest scores of spiritual well-being were that religion could assist people for well-being (4.28 ± 0.80), religious practices could assist people to find a peaceful life (4.25 ± 0.84), and a joyful life (4.25 ± 1.07). It can be explained by the fact that all of the participants were Buddhists. The Buddha’s words teach people to make merit, stop all bad acts, and clean their minds every day. Furthermore, Buddha’s words teach people “nothing is permanent” (impermanence, conflict, and soullessness). All humans cannot escape suffering from birth, old age, sickness, and death. Understanding these words by the Buddha can help people to accept every circumstance in their life.8,32 This understanding is very important to facilitate spiritual well-being among PLWHA. The result of this study was consistent with some previous studies.17, 21 ,33

Predicting factors among PLWHA

Predicting factors of spiritual well-being among PLWHA were hope, religious practice, and social support, accounting for 49.90% (p < 0.05).

Hope was a significant predicting factor of spiritual well-being among people living with HIV/AIDS (β = 0.446, p = 0.000). The reasons can be explained by the fact that hope is the source of spiritual well-being.34,35 Fisher,35 Highfield and Carson40 indicated that hope is an important factor for promoting spiritual well-being. Hope can assist PLWHA to find the meaning in life, to set goals, and achieve their goals. Hence, hope is a great drive for PLWHA to live well for the rest of their future life time. Chiyasit et al.,8 studied the roles of spirituality in PLWHA by using the qualitative meta- synthesis. The results revealed that spirituality plays a vital role in maintaining hope for PLWHA, which is important for them to confront physical and psychological distress and coming to terms with living with an incurable disease. According to previous studies of Netimetee18 and Khan,36 it was found that hope correlated positively with spiritual well-being among HIV/AIDS. Khan36 found that hope was a predictive factor of spiritual well-being among PLWHA accounting for 40.20%.

Religious practice was a significant predicting factor of spiritual well-being among HIV/AIDS (β = 0.188, p = 0.005). This might be explained because all participants were Buddhists. The level of religious practice was at a moderate level. They always give to charity, live by the five Buddhistpercepts (abstain from taking life, stealing, sexual misconduct, false speech and intoxication), and develop their mental faculties. These practices were important for improving inner strength, a sense of connectedness with a higher power, hope, and a peaceful life.8,17,25 O’Brien31 indicated that spiritual practice is important for finding spiritual meaning in the experience of illness. This is important for promoting spiritual well-being. The result of the study was consistent with previous studies. Religious practice predicted spiritual well-being among PLWHA, accounting for 69%.17

Social support was a significant predicting factor of spiritual well-being among HIV/AIDS (β = 0.225, p = 0.007). This may be explained as participants perceived the level of social support at a high level consisting of emotional support, esteem support, network support, tangible support, and information support. Although one-third of the participants were married, this may not mean that another status is less preferable, participants might choose to live alone because in the Thai cultural context people pay attention to family attachment. When family members are sick, other members take care of them with love.4,5,7,8,16-18 O’Brien31 indicated that social support from families, friends, and caregivers is beneficial for finding spiritual meaning in the experience of illness. This is important for promoting spiritual well-being. The result of the study was consistent with previous studies.16, 28, 37 Sitipran37 found that social support predicted spiritual well-being among PLWHA, accounting for 24.60%.

Depression levels related to spiritual well-being among PLWHA (r = -0.26, p = 0.002), is congruent with previous studies of Yi et al.,38 and Dalmida et al.,21 They found too that depression is associated with spiritual well-being among PLWHA. However, depression could not predict spiritual well-being among PLWHA. This may be explained as the level of depression among PLWHA was at the lowest and low level, by 92.76%, and the correlation between depression and spiritual well-being was a low correlation (r = -0.26). In addition, the mean time since HIV diagnosis was 9.64 years. This is a long enough period for PLWHA to adapt effectively to their illness.32,39 Hence, they perceived their depression at the lowest and low level. According to a study by Saeloo,39 it was shown that, after being diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, patients were able to accept HIV and death after around 1-6 years. Therefore, they live in harmony with life.

CD4 cell count was not associated with spiritual well-being among PLWHA (r = -0.17, p = 0.053).This may be explained as the mean time of taking ARV was 8.28 years and medication adherence was higher than 95% with 92.80%. This factor has a positive effect on increasing CD4 cell count from 207.93 cell/mm3 to 461.65 cell/mm3. Therefore, they perceived that they were healthy and their illness did not disturb their physiological and psychological functions. Mwesigire et al.,41 found that CD4 cell count was not associated with quality of life among HIV patients after taking ARV at six months. Participants perceived quality of life as happiness and well-being influenced by health status. However, the result of the study was different from the studies of Dalmida et al.,21 and Ironson & Kremer22. They found that CD4 cell count was associated with spiritual well-being among PLWHA.

The study was carried out at only one tertiary hospital located in northeast Thailand with a total of 138 cases of PLWHA. Thus, the findings of the study cannot be generalized to all PLWHA in Thailand.

The overall spiritual well-being of PLWHA was at a high level. Factors related to spiritual well-being of PLWHA were religious practice, social support, depression, and hope. There was no correlation between CD4 level and spiritual well-being among PLWHA. Predicting factors of spiritual well-being among PLWHA were hope, religious practice, and social support, accounting for 49.90%.

Hope, religious practice, and social support can predict spiritual well-being. Therefore, implementing intervention programs with a focus on the significant predicting factors to promote spiritual well-being among PLWHA is recommended. In addition, other factors influencing spiritual well-being should be explored in further research. For example, personal characteristics, personal faith, and spiritual contentment.

The research team wish to acknowledge the Faculty of Nursing, Ubon Ratchathani Rajabhat University for supporting funding for the study.