Airway stenosis is the partial or complete narrowing of the central airway passages. This may involve the subglottic, trachea-esophageal, broncho-esophageal or tracheo- broncho-esophageal area. The disease may be caused by focal inflammation or trauma (prolonged tracheostomy or intubation), systemic inflammation, infectious disease (Tuberculosis), or malignancy (primary or metastatic). It is a potentially life-threatening condition with varying signs and symptoms. Patients frequently do not recognize any symptom until at least 50% of the luminal diameter is compromised because of the distensible character of the esophagus. This explains the late presentation and or prognosis associated with the disease.1 Management requires immediate attention, thorough physical examination, diagnostic tests computed tomography (CT) scan, accurate diagnosis and ultimate definitive treatment. Though there are many types, causes and management of tracheal stenosis, this article focuses on six cases of adult airway stenosis and the team’s unique approach to each case.

We performed this study to analyze the different techniques used in handling six patients with different pathology/causes of airway stenosis. Between September 2012 and November 2013, we identified six patients diagnosed with central airway narrowing. All cases had symptomatic airway stenosis. We analyzed each case study, considered the pathology of the disease, treatment, prognosis, and improvement in quality of life.

A 46-year-old male patient diagnosed with stage III lung cancer. He was referred to our medical facility nine months after a right upper lobectomy and subsequent external irradiation and chemotherapy. The cytopathology report from the lobectomy revealed large cell undifferentiated carcinoma, suggestive of Adenocarcinoma with 90% tumor necrosis, with a dimension of 7.0×6.0×4.2cm.

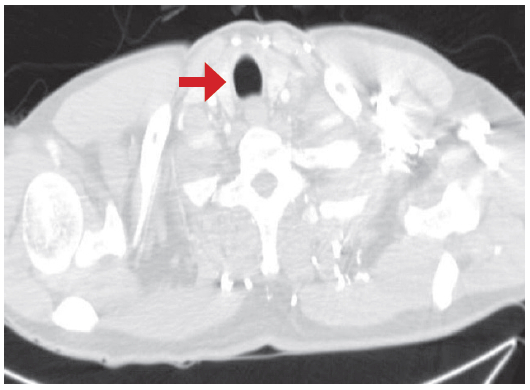

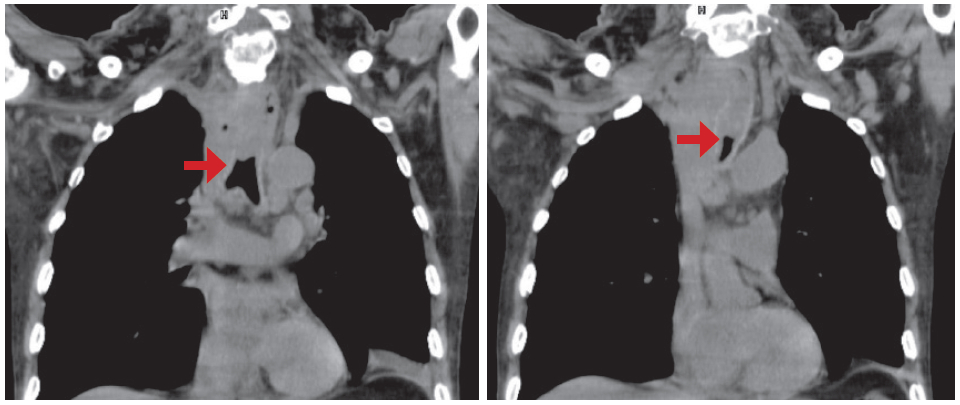

The physical examination revealed coughing for two months, progressive difficulty and shortness of breathing for two weeks, orthopnea, rhonchi upon auscultation of the lung and pain when in the right lateral position. No cardiac problems were noted. Neck, chest and abdominal CT scan presented a demon-strable consolidative mass with heterogeneous enhancement, central necroses, haemorrhage and lobulated contour; measuring about 82×48mm in the right lung apex, prevertebral and paratracheal regions. This mass extends to the pleurae, periphery, adjacent upper thoracic vertebrae, upper trachea & upper esophagus. The mass causes pressure that affects the upper trachea and upper esophagus which results in an upper tracheal stenosis/obstruction (more than 80-90%) (Figure 1A).

The patient was advised to undergo a bronchoscopic evaluation and insertion of a small endotracheal tube to establish patent airway. The direct visualisation of the location of the tumor was crucial (external or endobronchial in nature) in order to consider electrocautery in extraction of the mass or to establish if a stent placement were possible. A team of oncologists, anaesthesiologists, and a cardio-vascular surgeon were consulted regarding this scenario. The patient and relatives were made aware of the high risk of this procedure and possible complications, including complete airway obstruction, haemorrhage, infection, and mortality. The prognosis and better quality of life and alternatives were discussed. The patient and relatives acknowledged these but decided to delay the treatment.

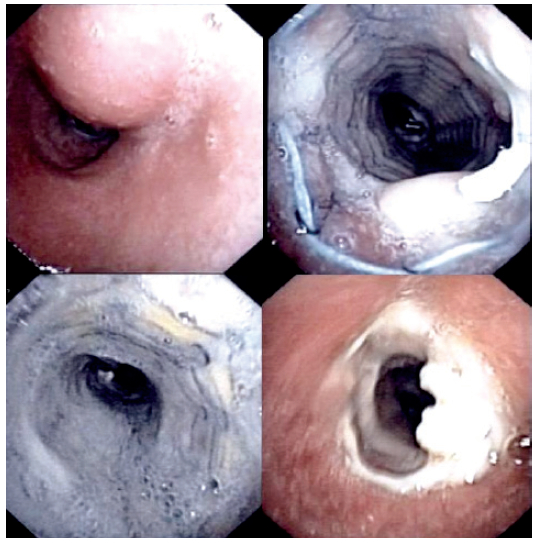

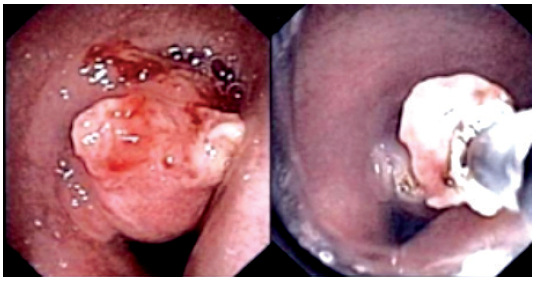

Two months after the initial consultation, after progression of symptoms, the patient decided to undergo the bronchoscopy and stent placement. Flexible bronchos- copy showed endobronchial mass nearly completely obstructing the main airway. A rigid bronchoscope was used for stent placement. A polyflex airway stent was successfully inserted and the patient did not manifest any complications (Figure 1B). In the succeeding months, the patient underwent brachytherapy for treatment. Three months post stent placement, the patient came back complaining of dysphagia. A PET/CT scan presented a continued increase in size of the mass at the superior mediastinum which extended to the right upper parame- diastinal region and partially encased trachea, now measuring about 6.9×5.2cm at the sternal notch level. The tracheal stent is in place from the sternal notch to the carinal level. The mass affects the proximal superior vena cava. The superior extension of this mass which extended beyond the apical lung, involved scalene muscle and involves compression to the right brachial plexus which also increased in size from 1.5cm to 2.3cm. He was then admitted to undergo a fiberoptic bronchoscopy and electrocautery to remove the tumor on both ends of the stent and to suction the mucus plug (Figure 2).

Post procedure, he was improving symptomatically with the infusion of antibiotics and palliative radiation therapy to the affected part of the tumor mass. The patient continued receiving treatment until he passed away eight months after the stent placement.

Figure 1A: CT scan demonstrating consolidative mass

Figure 1B: Shows (clockwise from upper right) part of the mass, the stent placement, mucous plug and tumor regrowth

The patient is a 46-year-old male who presented with progressive dyspnea for four months, hoarseness of voice and stridor for two months, fever, and cough with greenish secretions for two weeks. He was previously a smoker for 20 years but had stopped six months prior to consultation. The physical examination revealed stridor upon auscultation.

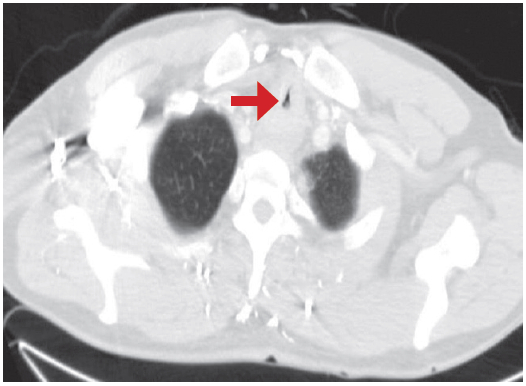

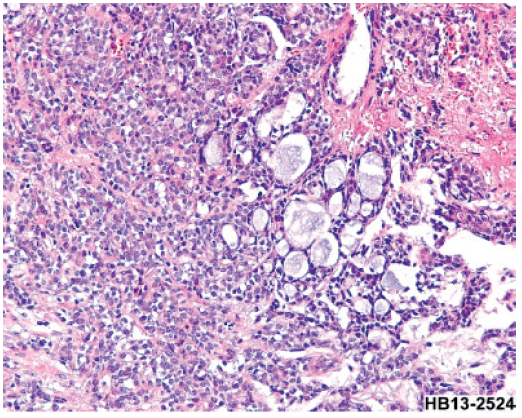

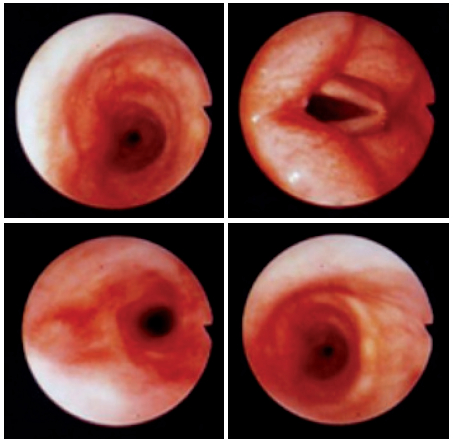

A chest CT scan revealed a thickened tracheal wall, more on the posterior wall about 5cm in length from about lower T1 to lower T4 level, causing narrowing trachea (Figure 2A-B). Multiple pulmonary nodules were noted (at least seven in the right and five in the left lung). Metastasis was suggested and the largest nodule near the right hilum may be a primary carcinoma. Laboratory markers were significant for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA): 5.49ng/mL, Hemoglobin: 11.4g/dL and WBC:13.54*10^3/mm3. The patient was then intubated with the use of a microlaryngeal tube no. 5 as the endotracheal tube no. 8 was unable to pass through. The plan was that once stable, the patient would undergo a FOB for tracheal examination, visualization, biopsy, and electro- cautery followed by stent placement with the use of a rigid bronchoscope. The risk of hypoxia was significant and recognized. Two days prior to the scheduled procedure, the patient exhibited hemoptysis. Bedside FOB was done to investigate and the cause of bleeding was stopped by electrocautery. The following day the patient exhibited bradycardia because of the sedative effects of anesthesia but this was controlled and managed properly. Then he underwent FOB which revealed tracheal stenosis due to the thickened endotracheal wall. Stent placement was done using a rigid bronchoscopy. A polyflex airway stent was successfully inserted. Specimens were sent to the laboratory for cytology and revealed that the tracheal tissue is positive for adenoid cystic carcinoma (Figure 2C).

Figure 2A: This shows the normal upper trachea

Figure 2B: Stenosis at the mid portion of trachea

Figure 2C: Adenoid cystic carcinoma as described in case # 2

This is a case of a 69-year-old male patient diagnosed with esophageal cancer with metastatic brain tumor status post craniotomy for removal of tumor. He was referred for co-management of a tracheal invasion. He was a known smoker for 10 years. He first complained of difficulty of breathing six months prior to consultation. The physical assessment revealed cough with whitish secretions, secretory sounds upon auscultation, dysphagia, abdominal discomfort, and episodes of fever. The neck and chest CT scan revealed a mass that invades the posterolateral aspect of upper intrathoracic trachea, causing an intra-luminal narrowing (6mm in anterior-posterior (AP) dimension) which also invades the posterior part of the right lobe of thyroid gland. A new lobulated contour subpleural nodule was also seen at the posterobasal segment of the right lower lobe, size = 2.1cm. A few millimeters of subpleural nodules were seen in the posterior segment of the right upper lobe, the apicoposterior segment of the left upper lobe, the superior segment of the left lower lobe, and the anterior basal segment of the left lower lobe. (Figure 3) Since the patient had been battling with metastatic brain cancer, palliative treatment of a stent placement was offered. Upon admission, the patient underwent a chest CT scan and the results revealed diffuse centrilobular nodules with interlobular septal interstitial thickening, multiple significant mediastinal lymphadenopathy and segmental esophageal mass (primary carcinoma); measuring about 6cm in length at the level of the cervico-thoracic junction. He was then scheduled for the operation and with the cooperation of the cardio vascular technologist (CVT), anaesthesiologist, and the operating (OR) team, the stent placement was done successfully. A fiberoptic bronchoscope was first used to suction secretions and help clear the airway then fluoroscopy to assess the location, and measure the size of the oesophageal mass. Electrocautery was performed to stop any source of bleeding followed by the insertion of the rigid brocho- scope for stent placement. Post procedure, the patient was intubated and was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for continuous monitoring. No hemoptysis, vomiting, or untoward complications were noted.

Figure 3: CT scan revealing a mass that invades the upper intrathoracic trachea

A 27-year-old woman, who is a foreign health care worker exposed to patients diagnosed of pulmonary tuberculosis, presented a productive cough with purulent sputum and right lateral chest pain in late 2012. Her acid fast bacilli (AFB) was positive and she was then diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis and underwent treatment for six months with the following course of drugs: Isoniazid, Rifampicin, Pyrazinamide and Ethambutol for two months then Isoniazid and Rifampicin for four months. Ten months later she presented stridor, wheezing, shortness of breath and dyspnea. The AFB was negative, the chest CT scan revealed atelectasis at the anterior and superior segments of the right upper lobe probably due to mucous impaction or aspergillosis in the bronchi and bronchioles. Bronchoscopy revealed narrowing in the near mid trachea (Figure 4A).

Figure 4A: Bronchoscopic findings showed narrowing in the near mid trachea

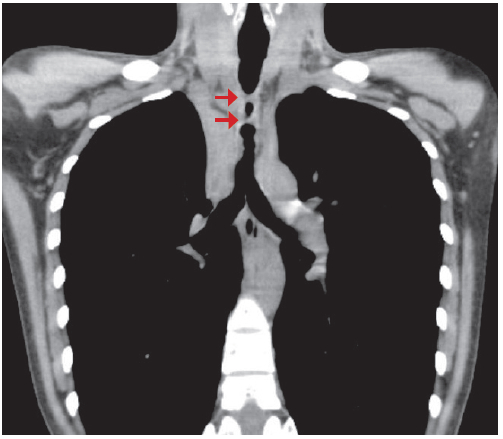

She was then diagnosed with tracheal stenosis. She was prescribed Prednisone 5mg tab and a Flixotide inhaler. Two months following her diagnosis, she visited our medical facility for a 2nd opinion. She was provided with two treatment options. The first was a tracheal reconstruction and the second was stent placement with the use of a silicone stent. Benefits and risks such as infection, bleeding, tracheoesophageal fistula, laryngeal nerve injury, dehiscence of suture line of trachea, restenosis and mortality were discussed. The patient decided to undergo a tracheal reconstruction. Neck and chest CT scans revealed tracheal narrowing; 25mm long segmental circumferential thickened wall (6mm thick) at middle portion of trachea (sternal notch level). The narrowest portion has right to left diameter of 3mm as the narrowest portion, with an Anterior-Posterior diameter of 6mm. The right lung presented atelectasis of the upper lobe with minimal calcification (Figures 4B-C).

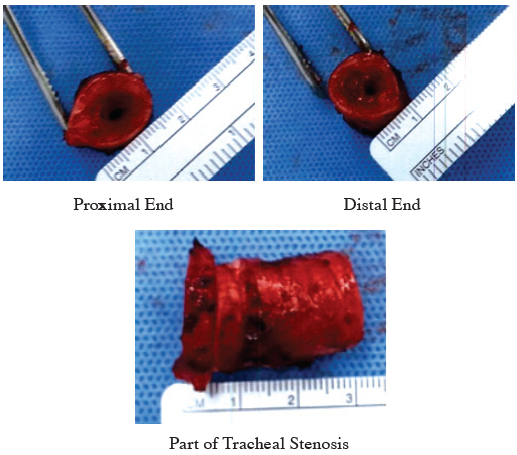

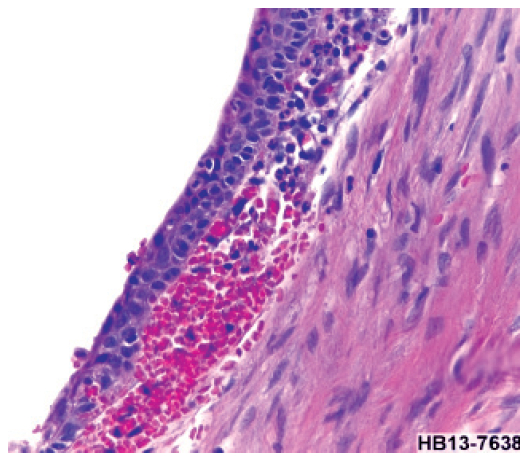

The patient underwent fiberoptic bronchoscopy first for direct visualisation before proceeding with the surgery. Tracheal resection and reconstruction under general anaesthesia were done. The stenotic parts of the trachea (proximal and distal end) were dissected and removed (Figure 4D). Post-surgery, she was admitted for observation. No untoward complications were noted and she was maintained on a neck flexion position. The cytopathology report from the tracheal tissue revealed that the trachea was lined by respiratory type mucosa with extensive squamous metaplasia. There are acute and chronic inflammatory infiltrates. The stroma shows fibrosis. There are no granulomas or viral inclusions. No evidence of dysplasia or malignancy noted (Figure 4E). The patient recovered well following the tracheal reconstruction surgery.

Figure 4B: Three-dimensional benign tracheal stenosis

Figure 4C: Three-dimensional benign tracheal stenosis

Figure 4D: The dissected stenotic part of trachea

Figure 4E: Squamous metaplasia with acute inflammation

The patient is a 41-year-old female from the Middle East, who presented dyspnea for two years. She has an underlying condition of bronchial asthma, for which she was taking Fluticasone Diskus 500mcg two times a day and Salbutamol Metered Dose Inhaler (MDI) for relief. For the preceding two years she has had frequent hospital admissions due to acute exacerbation of asthma. The chest CT scan revealed the presence of a lobulated well-defined soft tissue density. Endotracheal lesions were seen related to the anterior and right anterolateral walls of the distal trachea just above the level of the carina. It measures about 16×16×19mm along its maximum anteroposterior, transverse and craniocaudad dimensions respectively. A bronchoscopy with biopsy was advised for further evaluation. One month following the recommendation from her local physician, she sought medical consultation in our facility. The lung function test revealed severe obstruction without response to the bronchodilator.

A fiberoptic bronchoscopy was done and revealed a mid-endotracheal mass (Figure 5). The cytopathology from the biopsy presented the bronchial wall with chronic inflammatory cell infiltration without tumor cell or granuloma. Removal of the endotracheal mass and subsequent stent placement was advised for management. Benefits and risks such as tracheoesophageal fistula, hypoxia, bleeding and infection were discussed. The endotracheal mass was extracted via the combination of a rigid brochoscope and fiberoptic bronchosope with snare and electrocautery. She did not manifest untoward complications. The cytology report from the mass reveals unremarkable covering respiratory epithelial cells. The subepithelial element shows dense infiltration by mostly small lymphoid cells admixed with some plasmacytoid ones, plasma cells, and larger cells. Scattering secondary follicles were noted. There was no granuloma or necrosis.

The tumor panel concluded that the specimens must be sent to the laboratory for the following tests immunohistochemical stains for CD3, CD20, CD5, CD23, CD10, BCL6, BCL2, Ki-67, kappa, lambda, CD43, and cyclin D1 in order to determine if whether this is a lymphoma or a pseudo lymphoma.

Figure 5: The first photo shows the mid endotracheal mass as described in case #5 and how it was removed using bronchoscopy and snare electrocautery.

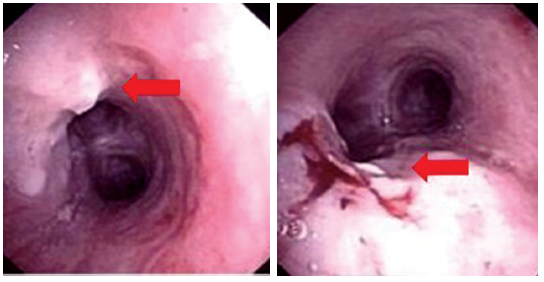

This is a case of a 37-year-old female who was referred to our medical facility due to chronic cough for 6 weeks and weight loss (1.5 kgs) that seem unresponsive to antibiotic treatment. She took Amoxicillin 250 mg 3 times for 5 days but did not respond well to the prescription. None of the laboratory test result showed significant elevation or abnormality. Chest x-ray even revealed a negative chest study. To further investigate, FOB was suggested to directly visualize the airways. After giving consent and observing standard pre- procedure protocols, she under- went FOB under IV sedation. An endotracheal tumor was observed and was subsequently extracted by performing biopsy then snare electrocautery (Figure 6). Post procedure, she did not manifest bleeding or untoward signs and symptoms. Three days after, the results came back negative for malignancy and fungal infection but positive for mycobacterium tuberculosis. She was then diagnosed with Tracheal Tuberculosis. She was given the following oral antituberculosis regimen: Isoniazid 100 mg tablet 3 tablets once daily, Rifampicin 600 mg tablet 1 tablet once daily, Ethambutol 400 mg tablet 2 tablets once daily and Pyrazinamide 0.5 gram tablet 3 tablets once daily. Initially, while on treatment, she complained of diarrhea. A stool exam was done and revealed negative results. At two weeks on treatment, she reported that she experiences less coughing, better appetite but still has occasional weakness. She was asked to follow up for after two weeks to check her liver function test.

Figure 6: The first photo shows the endotracheal tumor while the second image shows the tumor was successfully extracted with minimal bleeding.

1. Tracheal stenosis caused by Malignancy

Both malignant and benign diseases may cause focal narrowing of the tracheobronchial tree. Within the trachea, malignancy predominates.2 In July 2013, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that chronic diseases cause increasing numbers of mortality worldwide. Lung cancers (along with trachea and bronchus cancers) caused 1.5 million (2.7%) deaths in 2011, a remarkable increase from 1.2 million (2.2%) deaths in 2000. The vast majority of these types of cancers are diagnosed at a critical later stage when the disease has metastasized to other organs and or lymph nodes. Primary tracheal malignancies include squamous cell carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma, among others. Non-small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer are obvious causes of obstruction due either to extrinsic airway compression, intrinsic airway tumor, or a combination of both.2 A recent study in 2008 presented that in one series of 264 patients with malignant esophago-respiratory fistulas (ERF), 243 (92%) had esophageal cancer, 19 (7%) had lung cancer, and 2 (1%) had mediastinal tumor.3

Signs and symptoms vary depending on the location of the narrowing and nature of the disease. Patients complain of dyspnea, shortness of breath and dysphagia which is progressive, most of the time constant and unresponsive to bronchodilators. Wheezing maybe present and stridor can be heard especially for severe tracheal obstruction. The onset and progression of these signs and symptoms generally depend on the pathology and extent of the disease. In a study of 207 malignant trachea-esophageal fistulas (TEFs), signs and symptoms include cough in 116 (56%), aspiration in 77 (37%), fever in 52 (25%), dysphagia in 39 (19%), pneumonia in 11 (5%), hemoptysis in 10 (5%), and chest pain in 10 (5%).4 Surgical resection remains the gold standard for treatment of airway stenosis. However, most cancer patients are not medically fit and may have been diagnosed only in the later stages of malignancy. Palliative measures are offered to relieve worsening symptoms. Treatment includes chemo, radiation, brachytherapy, tumor ablation, endoscopic techniques, and stent placements. These options if successfully done may improve breathing, the swallowing mechanism and quality of life.

The latest standard therapy for cancer patients with airway stenosis is endoscopic or radiologic placement of endotracheal-covered self-expanding metallic stents (SEMS).5 A covered expandable endotracheal stent can relieve symptoms in more than 80% of patients with malignant stenosis.6,7 If performed early following diagnosis, this treatment may positively change quality of life and improve survival. Endotracheal stents can be inserted with the patient under general anesthesia via rigid or flexible bronchoscope with moderate sedation. The mean survival period of patients with ERF was 2.8 months in one study, but in patients with esophageal stents it was 3.4 months. With only supportive therapy, it was 1.3 months.3 Overall median survival times after diagnosis of ERF is only 8 weeks.8 Patients generally tolerate stent placement but close monitoring is needed so to assess complications ahead of time and manage appropriately. Potential issues include recurrence of obstruction, growth of granulation tissue, stent occlusion and migration, bleeding and infection. A recent study by Homann, et al. reported1 late complications in 71 of 133 stented patients (53.4%) with a quarter of patients experiencing several complications. Recurrent dysphagia connected to tumor ingrowth (22%), overgrowth (15%), stent migration (9%), and food bolus obstruction (21%) were the most common complications, followed by the development of esophago- airway fistulas (9%). Successfully re-treated patients had a markedly longer life expectancy compared to those who did not come back for further management. In an additional retrospective review of 97 patients with SEMS placement, dysphagia improved in 86% and trache-osophageal fistula symptoms in 90% of the patients.9

2. Benign cause

A variable degree of stenosis has been reported in up to 90% of patients with tuberculosis.10

The application of surgical resection to airway narrowing caused by benign disease requires meticulous cooperation with the anesthesiologist, pulmonologist, nursing staff and thoracic surgeon who have been well trained in the reconstruction of complicated tracheobronchial abnormalities. Surgery can be done for benign stenosis that affects less than half of the trachea. The type of surgery performed depends on the site of stenosis. Preoperative requirements include history, physical examination, radiographic imaging such as chest x-rays, CT scans and bronchoscopy results. The direct visualization provided by the bronchoscope will show the anatomy of the airway at the same time the affected parts of the stenosis. It is important to note the distance from the stenosis to anatomic landmarks in addition to the length of the stenotic segment and the status of the mucosa. Operation of the airway needs constant communication between the pulmonologist, surgeon and anesthesiologist. The steps of tracheal resection and reconstruction are the following: 1.) localize the diseased segment, 2.) mobilize the trachea, 3.) transect the trachea, 4.) resect the affected area, 5.) and reconstruct.11 Anastomotic complications are uncommon post operatively but may lead to serious complications. In one study conducted by Wright, et al. of 853 patients, 95% had a good result and 4% had an airway maintained by tracheostomy or T-tube. Tracheal resection with reanastomosis is seen as a procedure of choice given its high success rate (71%-95%) and minimal morbidity.12 It is usually successful and patients often fully recover from the operation.

Central airway stenosis is a life-threatening condition with severe pulmonary complications that may be caused by several factors. Patients diagnosed with airway narrowing often present with comorbidities that require medical attention. There are a number of factors considered in order to choose the appropriate treatment for the patient. These are nature of the disease, urgency for treatment, alternative procedures, current health status and improvement to the patient’s quality of life.

Treatment is individualized and the management of this condition requires technical expertise of thoracic surgeons, pulmonologists and anesthesiologists. If caught early, and treatment has been determined and planned following diagnosis, improvement to the quality of life and potentially survival rates, may be achieved.