The prevalence of major depression in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) was between 17 and 27%.1,2 Depression was also found to be about 3 times more common in patients after an acute myocardial infarction.3 Compared to individuals with no history of depressive conditions, patients with depressive conditions had frequently higher levels of biomarkers that predicted cardiac events or promoted atherosclerosis. In fact, several studies in depressive patients have shown reduced heart rate variability (suggesting an increased sympathetic activity and/or reduced vagal activity)4, evidence of increased plasma platelet factor 4 and beta thromboglobulin (suggesting enhanced platelet activation) 5,6 impaired vascular function7, increased C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and fibrinogen levels (suggesting enhanced inflammatory response).8,9

Patient population

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects’ Research of the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) Medical College and Vajira Hospital. Written informed consent was given by all the study participants and all the consent forms were collected before the study began. A total of 134 stable CAD patients who came to the cardiovascular OPD clinic at BMA medical college and Vajira Hospital between August 2011 and January 2012 took part.

Exclusion criteria were patients with: 1) acute coronary syndrome (unstable angina, myocardial infarction or revascularization) or congestive heart failure 2) a history of recent cardiovascular surgery within the preceding 3 months 3) patients who were diagnosed as having a history of depressive disorders or other psychiatric diseases before enrollment and 4) patients who did not wish to participate.

The stable CAD patients’ complete medical history was evaluated. Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) Thai version was used to assess depressive symptoms, score of 10 or higher was diagnosed as depression. This scale was shown as acceptable for reliability and validity.15 The screening test was patient self-rated an could be completed within 5 minutes or less.

Follow-up

The sample was classified into two groups according to the MADRS score on initial enrollment: patients with a MADRS score > 10 were classified as the depressive disorder group. All patients were followed up for 6 months after their initial enrollment. The major cardiovascular end points studied were: 1) cardiac death 2) acute myocardial infarction 3) percutaneous coronary artery revascularization (PTCA) 4) coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) and 5) acute ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Hospital records, out-patient clinical records and interviews with the patient or primary physician were used to confirm each event.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as the mean value ± SD. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered significant. The correlation test was analyzed using the Pearson Correlation method. The data was analyzed by statistics software, compatible with Microsoft office.

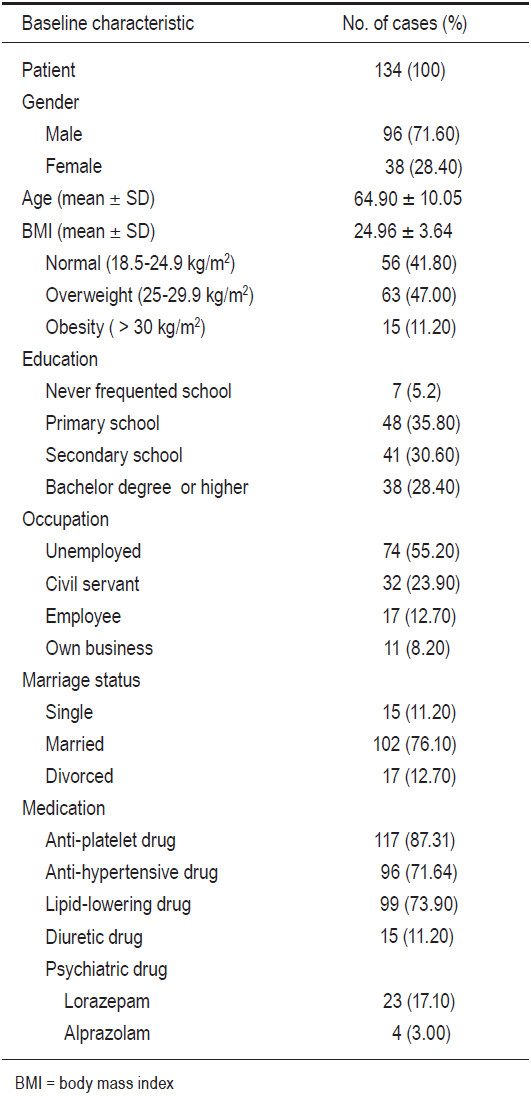

The 134 cases with stable CAD that were included in this study were followed up at the OPD clinic. All the participants had stable clinical symptoms during the study period. We found that the prevalence of depressive disorders in this study was 15%. The baseline characteristic of patients was: 71% male and 29% female. Fifty-six patients (41.8%) were of normal weight, whilst 63 patients (47%) and 15 patients (11.2%) were overweight and obese respectively (see Table 1).

Table 1: Clinical characteristics and laboratory parameters of the study group (n = 134).

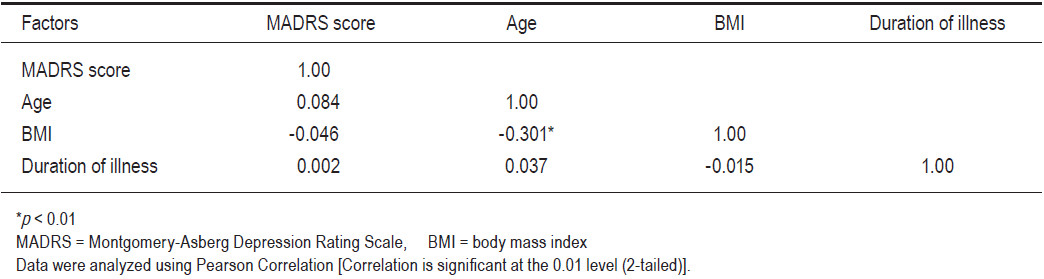

Table 2: Correlation between factors (age, BMI, duration of illness) and MADRS score (n =134).

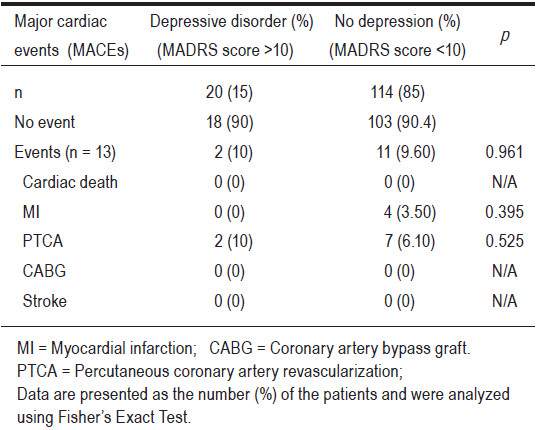

Table 3: MACEs in the depressive and non-depressive group.

Half of the patients were unemployed and received financial support from their family. Most of them were on medications such as: anti platelet and anti-hypertensive drugs and lipid lowering drugs for the treatment of their co-morbidity conditions. But only around 20% of them had received psychiatric drugs (23 patients had been administered lorazepam and 4 patients had been administered alprazolam). Of the twenty-seven patients who had been treated with psychotropic drugs we also found that only seven patients (35%) of the depressive disorder group had been given anxiolytic but not anti-depressant drugs. We found that twenty (18%) of the participants in the non-depressive disorder group had been over-treated with anxiolytic drugs. Any negative correlation between BMI and age is shown in Table 2.

During the six months of the follow-up period, neither group had a cardiac death among them. That said, myocardial infarction was seen in the normal MADRS group (Four cases (3.5%)) but none were evident in the depressive disorder group. Two cases (10%) of the depressive disorder group and seven cases (6.10%) of the non- depressive disorder group had percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA); p = 0.525. CABG or stroke was not found in either group (see Table 3). There was no statistically significant difference in incidences of cardiovascular events (MACEs) in both groups (10% vs.9.6%; p= 0.961).

This study shows that depression occurred in about 15% of patients with stable CAD. Only 20% of patients were treated with psychotropic medications. Surprisingly, all of them were prescribed anxiolytic medications for the treatment of depression, but none of them had received anti-depressants.

A meta–analysis of 22 prospective studies found that post-MI depression leads to two-fold increase in the risk of death, cardiovascular death, and cardiovascular events.16 Similar to previous studies, Smith NS et al.17 found that in patients with stable CAD, diagnostic and dichotomous self-report measures of anxiety and depression predicted an increased odds ratio of experiencing MACEs in the long term 2 year follow-up period. However, the results of our study are not relevant to previous ones; this might be due to the short study period. Therefore, the factor of time should be taken into consideration in future studies to allow for comparative assessments to other studies.

There are some limitations of our study. Firstly, although the range of this study was adequate, the sample size was relatively small. Secondly, the short term follow-up period might be considered as a limitation. Future efforts should focus more on assessing a larger sample size and a longer follow-up period.

The recommendation from this study is that cardiologists should be more alert to the factor of depression and should provide more appropriate treatment management protocols; this remains true regardless of whether the cardiologists treat the depression of their patients themselves, or if their patients are referred to psychiatric healthcare providers who are qualified in assessing and treating depression.

Though the MACEs in this study were not statistically different in both depressive and non-depressive groups, the study showed a high prevalence of depression in patients with CAD. Therefore, cardiologists need to raise their awareness of this and to administer and manage depression properly. A longer study period and a larger sample size are recommended for future studies.

Conflict of interest: There is no conflict of interest in this study.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Bangkok Metropolitan Adminis- tration Medical College and the Vajira Hospital Research Fund and Clinical Research Center for their support of this study .We are also grateful to all patients and all nursing staff working at the Cardiovascular Unit for their co-operation in this study and their dedication to the care of these patients.