Head and neck cancers are common and regarded as one of the top public health problems in Thailand. According to Public Health Statistics issued in 2011 by the Department of Medical Service of the Ministry of Public Health, the number of lip, oral and pharyngeal cancer patients was the second highest number of all cancer patients receiving medical treatment.1 Moreover, this number is likely to increase because people tend to engage in high risk behavior such as alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking.2

Radiation therapy is an effective treatment for head and neck cancers. Although radiation therapy destroys cancer cells, it damages normal cells as well, causing side effects. The side effects of radiation vary from person to person depending on the size, location of the area being treated, and the amount of radiation. Patients with head and neck cancers, such as nasopharyngeal, oral cavity, laryngeal, and tongue cancers, may experience particular side effects because they receive radiation to the face and neck. Additionally, head and neck cancer patients treated with curative intent must be exposed to high doses of radiation. Thus, these patients may experience side effects and acute complications including sore throat, mouth sores, mucositis, dry mouth, and taste loss.3-6 The patients may develop chronic or subsequent complications such as mouth stiffness, jaw stiffness, limited mouth opening, and stiff neck.7-9 These symptoms can lead to loss of appetite and malnutrition.

Besides, there will be more side effects if a patient is given chemotherapy combined with radiation therapy.10 This will affect the patient’s nutritional status since the patient might not receive sufficient essential nutrients, especially during treatment. This results in weakness, weight loss, fatigue, impaired immune system, and complications during treatment such as anemia and infections. Due to these side effects, some patients have to postpone radiation therapy and some patients have to discontinue their treatment. The cancer control programs and survival rates are also affected. Therefore, nutritional care is an important factor behind the outcomes of radiation therapy in cancer patients, their recovery, and quality of life.

Nowadays, when patients receiving radiation therapy suffer from side effects which cause them not to have enough food or not be able to eat, they will receive nutritional care by TPN or ETF, which is divided into nasogastric tube feeding and gastrostomy tube feeding. The nutritional care can help patients receive treatment according to the plan without radiation dose adjustment, postponing and discontinuation of chemotherapy. A study by Naiyana P.11 found that, among 20 head and neck cancer patients who received nasogastric tube feeding, 4 patients gained weight, 16 patients lost weight, and only 1 patient lost more than 10% of their body weight. However, there was no patient who discontinued treatment. This showed that nasogastric tube feeding can help improve a patient’s nutritional status and it is beneficial for the doctor’s treatment planning.

The radiotherapy service at Wattanosoth Hospital is a specialized department offering radiotherapy services for a private tertiary-care cancer hospital with a focus on patient-centered care. It is found that many patients refuse ETF during radiation therapy because they are distressed by the change in their body image. It also affects their lifestyle, routine activities, and quality of life. Due to an awareness of this issue and the fact that there has been no research on nutritional care of head and neck cancer patients in a private hospital, the researcher decided to conduct a comparative study of the effectiveness of nutritional care between self-oral intake and ETF and/or TPN to find out whether the types of nutritional care have an effect on treatment planning and nutritional status in head and neck cancer patients. It is hoped that the results will be applied to provide some guidelines to nutritional care in head and neck cancer patients who are receiving radiation therapy and concurrent chemotherapy and radio- therapy in the future.

This research is a retrospective descriptive study. The target population was head and neck cancer patients who received radiation therapy at Wattanosoth Hospital. The sample was 58 head and neck cancer patients who received radiation therapy at Wattanosoth Hospital between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2011. The inclusion criteria were age > 18 years and complete medical records of radiotherapy. The exclusion criteria were death during radiation treatment.

The research instrument collected data from a medical records review. The data consisted of 3 parts:

Data collection

The hospital database system was searched for a list of head and neck cancer patients who received radiotherapy. Then, eligible patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were enrolled in this study. The patient data, radiation therapy data and nutritional status data were acquired from medical records and the hospital database system.

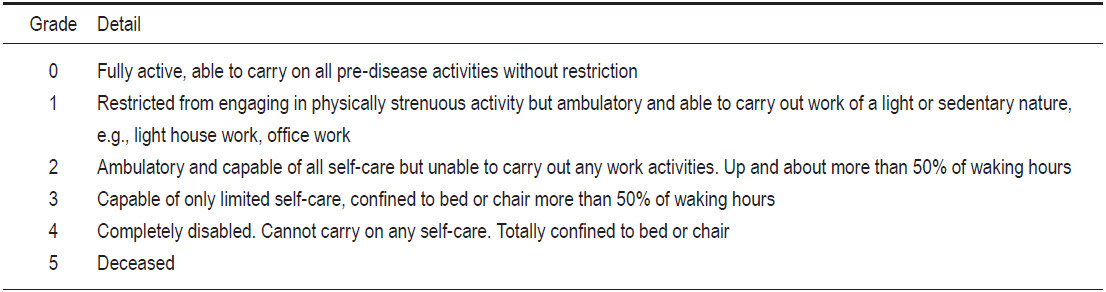

Table 1: Performance Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Status.12

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed by using a statistical software package. The statistically significant difference in patient data, radiation therapy data and nutritional status data between the self-oral intake group and the ETF and/or TPN group was examined by using a chi-square test, at p < 0.05.

There were 58 patients in total. The numbers of patients with self-oral intake and patients with ETF and/ or TPN were 34 (58.6%) and 24 (41.4%), respectively. In the ETF and/or TPN group, 17 patients (29.31%) received TPN, 3 patients (5.17%) received ETF, and 4 patients (6.90%) received ETF and TPN.

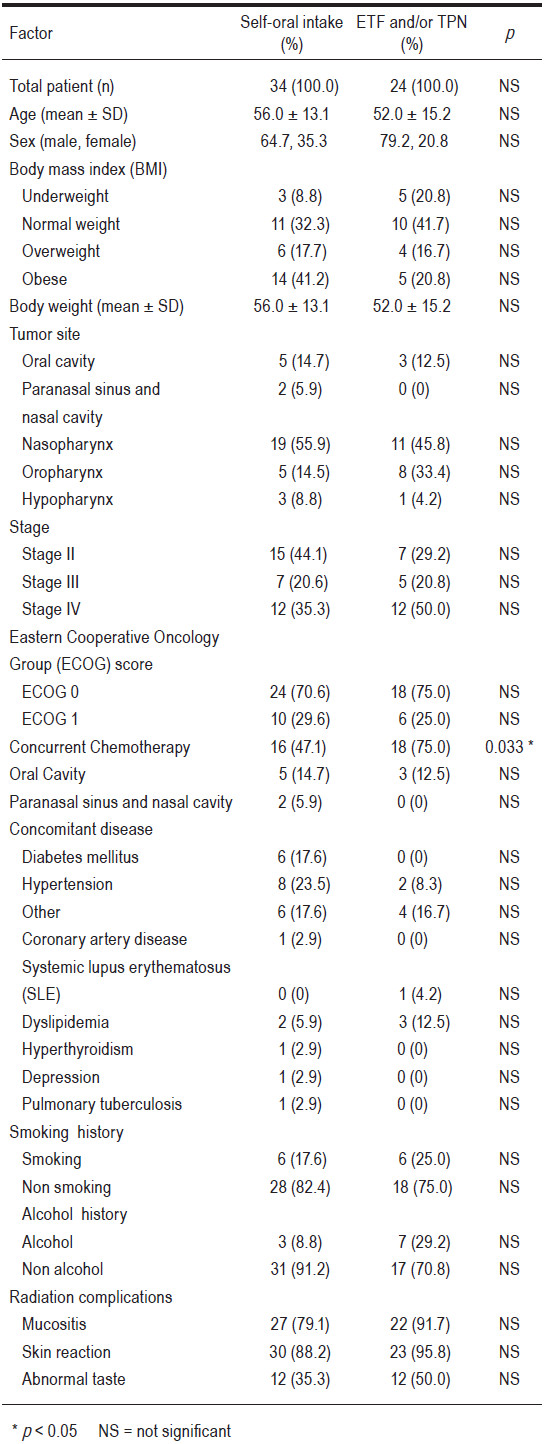

Comparisons between patients with self-oral intake and patients with ETF and/or TPN show no significant statistical difference. The personal information including age, sex, BMI, tumor site, ECOG performance status, oral cavity, paranasal sinus and nasal cavity, concomitant disease, smoking history, alcohol history, and radiation complications also shows no difference (statistically significant at 0.05). Only radiation therapy combined with chemotherapy (concurrent chemotherapy) shows a signifi- cant difference at p = 0.033 with parenteral and/or enteral feeding outnumbering the oral feeding as shown in Table 2. There was no difference in the patient data between the self-oral intake group and the ETF and/or TPN group, except concurrent chemotherapy which differed significantly at p = 0.033 as shown in Table 2.

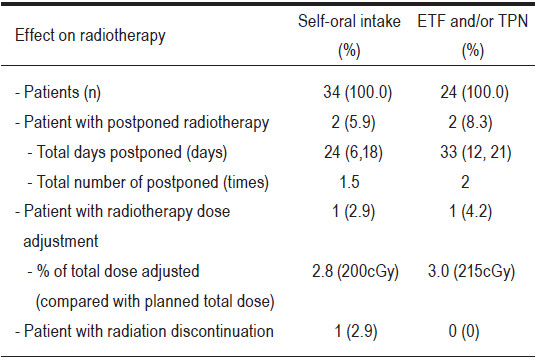

No significant differences were found in the number of times of postponed radiotherapy, the number of days of postponed radiotherapy and radiation discontinuation before completing radiation between the self-oral intake group and the ETF and/or TPN group at p > 0.05 (see Table 3). However, among 4 patients who postponed radiotherapy, 2 patients had to change their radiation masks in stage 2 of treatment due to side effects from concurrent chemotherapy at mild-moderate level. One patient in this group suffered from gastrointestinal (GI) side effects from concurrent chemotherapy at mild- moderate level during the last week of treatment. The last patient had side effects from concurrent chemotherapy at moderate-severe level.

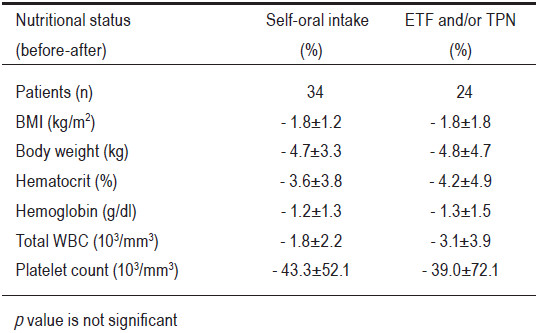

There were no significant differences in body weight, BMI, Hb, Hct, WBC Count, platelet count both before and after receiving nutritional care between the self-oral intake group and the ETF and/or TPN group at p > 0.05 (see Table 4).

Table 2: Comparison of patient data between the self-oral in take group and the enteral tube feeding (ETF) and/or total parenteral nutrition (TPN) group.

Table 3: Comparison of the effect on radiotherapy between the self-oral intake group and the enteral tube feeding (ETF) and/or total parenteral nutrition (TPN) group.

Table 4: Comparison of nutritional status before and after receiving nutritional care between the self-oral intake group and the enteral tube feeding (ETF) and/or total parenteral nutrition (TPN) group.

The study in nutritional care in head and neck cancer patients treated with curative intent or concurrent chemotherapy, both self-oral intake and enteral tube feeding (ETF) and/or total parenteral nutrition (TPN), did not affect radiation treatment planning and the patient’s nutritional status. A possible explanation for this might be that most cancer patients at Wattanosoth Hospital are wealthy, and thus they enjoy good health and nutrition. This is reflected in the good to excellent performance ECOG status. There were a total of 58 patients in this study. Among the patients who had ECOG Performance Status of 0, there were 24 patients with self-oral intake and 18 patients having ETF and/or TPN (total of 42 patients, 72.4%). There were 16 patients with ECOG performance status of 1, or 27.6%. Among these were 10 patients with self-oral intake and 6 patients having ETF and/or TPN.

Also, all of the patients in Wattanosoth Hospital were assessed for oral care, cleanliness in the mouth, and prevention and relief of oral mucosa inflammation by nurses. Moreover, patients were evaluated and a nutritionist planned the patients’ nutritional intake both for suitable taste and amount of nutrition received. Doctors also cared for any side effects evident in the oral cavity and throat.All of these cares were performed before, during and after radiation treatment periodically. The side effects were also reduced by the use of modern technology to minimize the unnecessary radiation dose in major organs associated with eating, especially the salivary gland and oral cavity. In addition, there were a small number of patients in this study and the data was collected over a short duration, which results in inadequate statistical accuracy.

The results show no significant difference in radiotherapy planning and nutritional status of head and neck cancer patients between patients with self-intake and patients having enteral tube feeding and/or total parenteral nutrition in case of ECOG scale 0-1 only. Therefore, enteral feeding or total parenteral nutrition before radiation treatment does not have sufficient supporting data. However, head and neck cancer patients receiving radiation treatment should be provided suitable and adequate nutrition. Especially those patients who have adverse reactions from radiation such as a sore throat, pain in the mouth and significant malnutrition. The consideration of applying enteral or parenteral feeding is therefore still necessary. It is recommended to take into account the potential impact on the patients’ physical and psychological well-being,and to assess each patient in a holistic way.

Limitations: As this research is a retrospective descriptive study and the data is collected from medical records and the hospital database system, there is a limited amount of data and some related data is neither comprehensive nor complete. In addition, the sample size was small and the data collection period was limited. Therefore, the generalization of the findings and the ability to analyze the results of the study are limited as well.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr. Niwat Boonyean (Medical Director), Dr. Chanawat Tasaviboon (MD) and staff of radiation services at Wattanosoth Hospital. The author is also grateful to Dr. Pravich Tanyasitisoonthoon and staff of BDMS Bangkok, Thailand for all their support towards this project.